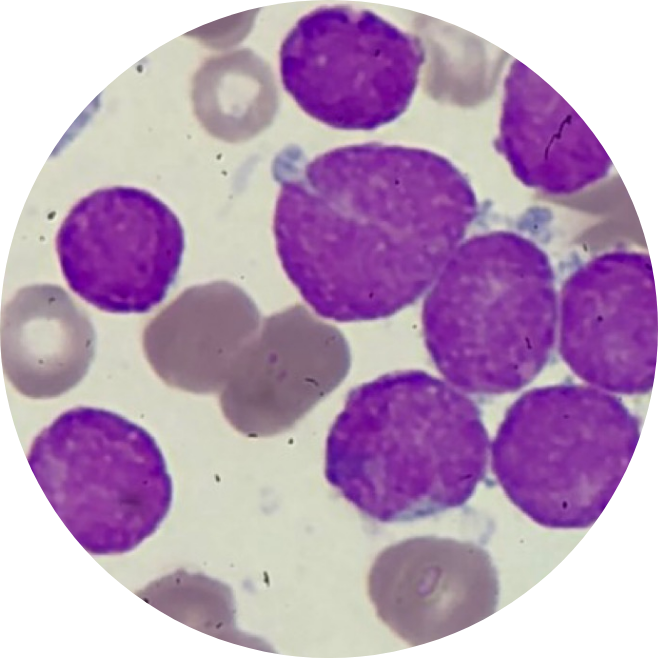

Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (pALL) is the most common type of blood cancer diagnosed among children.1 In a child with pALL, the bone marrow makes too many lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell. When this happens, these cells fill up the bone marrow and stop it from making the usual amount of healthy blood cells. Thus, affecting the body’s ability to defend itself and putting the child at increased risk of infection.

“Acute” means that this type of cancer is aggressive in nature and usually gets worse rapidly if it is not treated immediately.

As part of the body’s immune system, B cells are natural defenders of the body. When B cells become cancerous, they can grow out of control and cause a type of blood cancer called B-cell pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (pALL).2

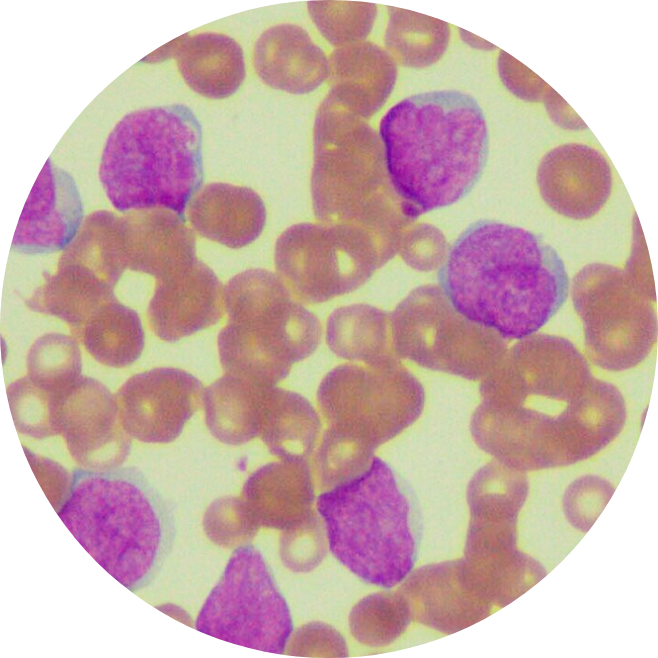

In pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (pALL) patients, abnormal cells in the bone marrow limit the production of red blood cells which carry oxygen, other types of white blood cells, and platelets. As a result, pALL patients may be anemic, more likely to get infections and bruise or bleed easily.3 While many children with pALL recover after their first treatment, some don’t.4

Did you know? According to World Health Organization (WHO), 55,767 cancer cases5 were diagnosed in Southeast Asian children aged 0-14 years old in 2020.

To determine if a person has pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (pALL)6, the doctor will ask about the person’s medical history, the family’s medical history, followed by a physical exam to look for possible signs of the disease, such as swollen lymph nodes.

First, a blood test is drawn to check the blood cell counts, liver and kidney function. If the results show a high number of abnormal white blood cells, it could be a sign of pALL. Your care team may then refer you to a hematologist to help guide the next steps of treatment.

To confirm a diagnosis of pALL, a sample from the bone marrow is taken for further testing. Imaging studies, such as X-ray scans, CT scans, MRI, or ultrasound, may also be done for a better understanding of where the leukemia cells have spread.

The lack of healthy blood cells causes most symptoms of pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (pALL). Common Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia symptoms to look out for include7:

In some cases, the affected cells can spread from the bloodstream into the central nervous system. Thus, causing neurological symptoms (related to the brain and nervous system), including headaches, seizures or fits, blurred vision, and dizziness.

Risk factors refer to anything that increases one’s risk of getting cancer, but they do not determine the diagnosis as Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (pALL) patients may have few or no known risk factors. According to statistics, the risk for developing pALL is highest in children below 5 years old.19

Factors within your control

Factors outside of your control

Studies have shown that with the proper treatment, patients with Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (pALL) have:

About 20% of patients with B-cell Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (pALL) will not have success with initial treatments.11 This means their cancer did not respond to treatment (refractory Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia).

Some patients who had recovered or seen a decrease in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia symptoms later report having a lower number of normal blood cells while also seeing a return of leukemia cells in their bone marrow. This means their cancer has returned (relapsed Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia).

In the past, the treatment options for patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (pALL) included chemotherapy, radiation, or stem cell transplant. Since then, scientific advances and medical research have opened doors for new treatments, such as CAR-T cell therapy.

In cancer care, treatment options and recommendations depend on several factors12, including the subtype and classification of Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (pALL), possible side effects, age, and overall health. It is best to consult with your care team on what is the best journey for your child.

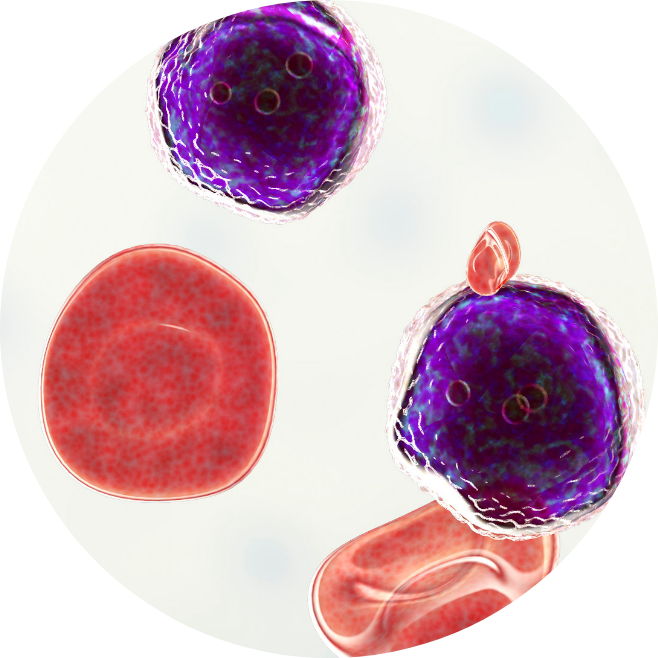

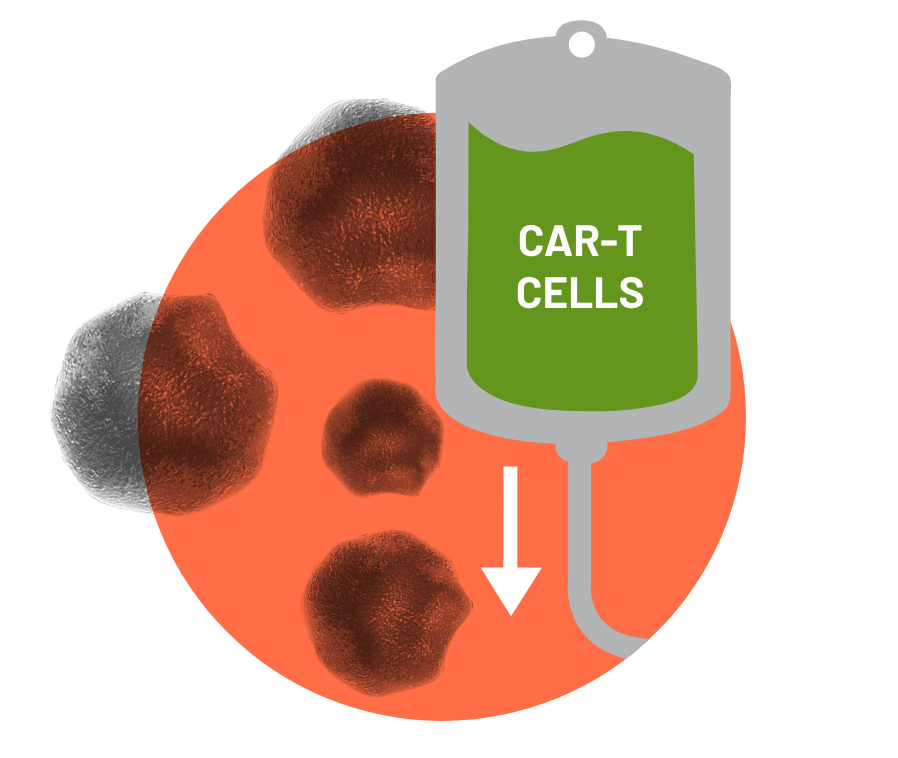

CAR-T cell therapy, or Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell therapy, is a type of immunotherapy that enhances the body’s natural ability to treat cancer by using modified T-cells.

CAR-T cell therapy involves altering the body’s T-cells, a type of white blood cell found in the immune system, with new receptors. This receptor is called a Chimeric Antigen Receptor, or CAR, and helps to target and stop the spread of cancer cells in the blood.

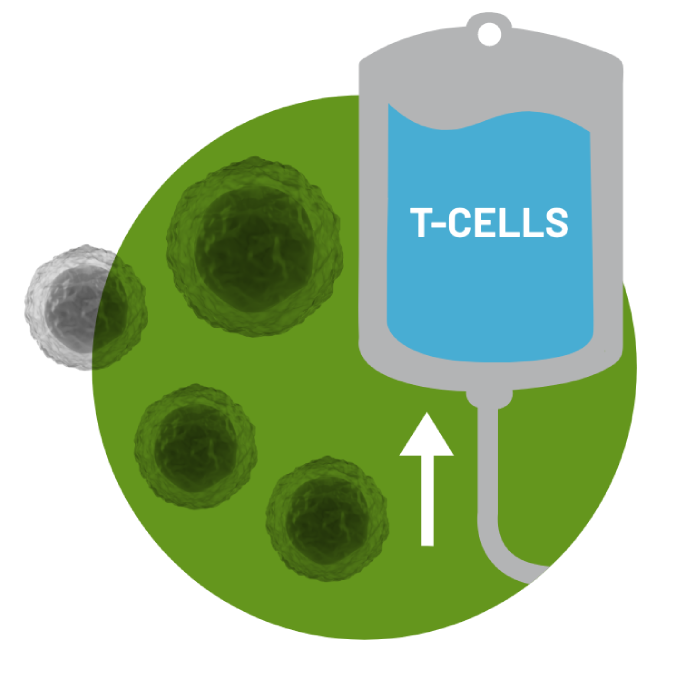

In order to collect the T cells, the patient's blood is drawn through a process called Leukaphereis. This process takes 3-6 hours in order to extract the T cells from the body.

Patient’s collected T-cells will be reprogrammed into CAR-T cells at a specialized manufacturing facility. The process usually takes 3 to 4 weeks, but timing and manufacturing outcomes can vary.

Before infusion, the physician decides if a short course of chemotherapy is needed to prepare the body. Once the treatment team decides the patient is ready, the patient will receive CAR-T cells through a single infusion that takes less than 30 minutes. At this stage, the increase in CAR- T cells may enhance the patient's immune competence (or their ability to withstand) against cancer cells.

In the short term, regular monitoring to manage side effects is essential. Whether the infusion was received in an inpatient or outpatient setting, it will be necessary to stay close to the treatment center for at least 4 weeks.

In the long term, the treatment team will establish a monitoring plan for ongoing follow-ups. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends that all patients be followed for 15 years after infusion. The treatment team will offer the patient participation in a long-term registry conducted by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) for this follow-up. This information is used to help future patients and contributes to understanding the effects of CAR-T cell therapy in the real world outside of clinical trials.

CAR-T cell therapy stands out from other cancer therapies because it is an individualized therapy made just for the patient.

Each patient’s infusion is created from the T cells in their own immune system. CAR-T cells may remain active in the body and act as a “living drug” to stop the growth of any new cells that may grow cancerous.20 Long-term data suggests that some patients recovered within months of treatment, meaning all signs and symptoms of their leukemia has disappeared.

Unlike other treatments, CAR-T therapy is designed to be a one-time treatment either with or without hospitalization (and may be done in an in-patient or out-patient setting).In most cases, a short course of chemotherapy is needed to prepare your child’s body for infusion.

CAR-T therapy does not require a donor as it uses one’s own cells for treatment. Thus, it is helpful for patients who may be ineligible for stem cell transplant due to other co-morbidities, while not bearing the risks associated with a transplant. It is considered a widely studied and safe option.

CAR-T cell therapy might be the next step if the initial treatments have not been working and the cancer has returned. It’s important to seek a second opinion to determine if CAR-T cell therapy is right for your child.

T cell health declines over time and is also affected by additional lines of treatment, such as chemotherapy, which then lowers your child’s overall response rates to CAR-T therapy.

Due to the aggressive nature of the disease, T cells collected in earlier stages can lead to better outcomes and a higher chance for complete recovery.24 T cells can be cryopreserved for up to 2 years.

Brown, P., et al. (2020). Pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia, version 2.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network: JNCCN, 18(1), 81–112. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2020.0001

A Caregiver’s Guide to Kymriah Therapy, 2019 (11/19, KYM-1223352) – extracted from Novartis resource

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). (n.d.-b). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Kidshealth.org website: https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/all.html

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). (n.d.-a). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Stjude.org website: https://www.stjude.org/disease/acutelymphoblastic-leukemia-all.html

Searo (south–east Asia region). (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Who.int website: https://www.who.int/cancer/countryprofiles/SEARO_profile082020.pdf

Tests for acute Lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Cancer.org website: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/detection-diagnosis-staging/how-diagnosed.html

Signs and symptoms of acute Lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Cancer.org website: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/detection-diagnosis-staging/signs-symptoms.html

Risk factors for acute Lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Cancer.org website: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html

Paediatric Cancer. (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Com.sg website: https://www.ncis.com.sg/Cancer-Information/About-Cancer/Pages/Paediatric-Cancer.aspx

Yi, M., Zhou, L., Li, A., Luo, S., & Wu, K. (2020). Global burden and trend of acute lymphoblastic leukemia from 1990 to 2017.Aging, 12(22), 22869–22891.doi:10.18632/aging.103982

What is Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia? (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Kymriah.com website: https://www.us.kymriah.com/acutelymphoblastic-leukemia-children/about-b-cell-all/understanding-b-cell-all/

Leukemia – acute Lymphocytic – ALL – treatment options. (2012, June 25). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Cancer.Net website: https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/leukemia-acute-lymphocytic-all/treatment-options

Chemotherapy for acute Lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Cancer.org website: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acutelymphocytic-leukemia/treating/chemotherapy.html

What you should know about acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Kucancercenter.org website: https://www.kucancercenter.org/news-room/blog/2020/10/what-you-should-know-acute-lymphoblastic-leukemia

Relapse in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL). (2019). Leukaemia Care.

Cleveland Clinic Cancer. (n.d.). Chemotherapy resistance. Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Chemocare.com website: https://chemocare.com/chemotherapy/what-is-chemotherapy/what-is-drug-resistance.aspx

Radiation therapy for acute Lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Cancer.org website: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/treating/radiation-therapy.html

Targeted therapy for acute Lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Cancer.org website: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/treating/targeted-therapy.html

Stem cell transplant for acute Lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Cancer.org website: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/treating/bone-marrow-stem-cell.html

T, J. (2011). Stemcell Transplantation- Types, Risks and Benefits. Journal of Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 01(03). doi:10.4172/2157-7633.1000114

Acute Lymphocytic leukemia (ALL): Stem cell transplant. (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Rochester.edu website: https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?contenttypeid=34&contentid=BALLT12

Immunotherapy for acute Lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). (n.d.). Retrieved March 11, 2022, from Cancer.org website: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/treating/monoclonal-antibodies.html

CAR T Patient & Caregiver Guide, Frankly Speaking About Cancer, Cancer Support Community and Gilda’s Club, Chapter 1 Page 2

Künkele,A,.Brown, C., Beebe, A., Mgebroff, S., Johnson, A, J., Taraseviciute, C.mA., Rolcyzynski, L.S., Chang, C.A.,Finney, O.C., Park, J. R., & Jensen, M.C. (2019). Manufacture of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells from Mobilized Cryopreserved Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Units Depends on Monocyte Depletion. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 25(2), 223-232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.10.004

Disclaimer:This is global website for information on CAR-T Cell Therapy and is intended for Patients and Caregivers outside the US. The information on the site is not country specific and may contain information that is outside the approved indication in the country in which you are located.