What is Diffuse Large B-Cell

Lymphoma (DLBCL)?

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) is a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (blood cancer) that affects the cells and organs of the immune system. There are different types of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), including high-grade B-cell lymphoma and DLBCL that arise from follicular lymphoma.1

What is Diffuse Large B-Cell

Lymphoma (DLBCL)?

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) is a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (blood cancer) that affects the cells and organs of the immune system. B cells, T cells and glands called lymph nodes make up the body’s immune system.

Sometimes, the cells inside a lymph node can grow abnormally and become cancerous.

Patients with Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) have abnormal (cancerous) B cells in their lymph nodes, and potentially in other parts of the body. DLBCL is often a very fast-growing (aggressive) form of lymphoma.1

Did you know?

- 1 in 5 people develop cancer during their lifetime2

- Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) is a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, one of the most common blood cancers

- Although Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) can occur at any age- the median age of diagnosis is 66 years3

- 5 year survival rates decrease by age4

- 78% 5-year survival rate for those aged 55 and below

- 54% 5-year survival rate for those aged 65 and above

How is Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) diagnosed?5

To determine if a person has Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL), your care team will ask about your treatment history, followed by a thorough physical exam to look for possible signs of the disease, such as swollen lymph nodes at various parts of the body.

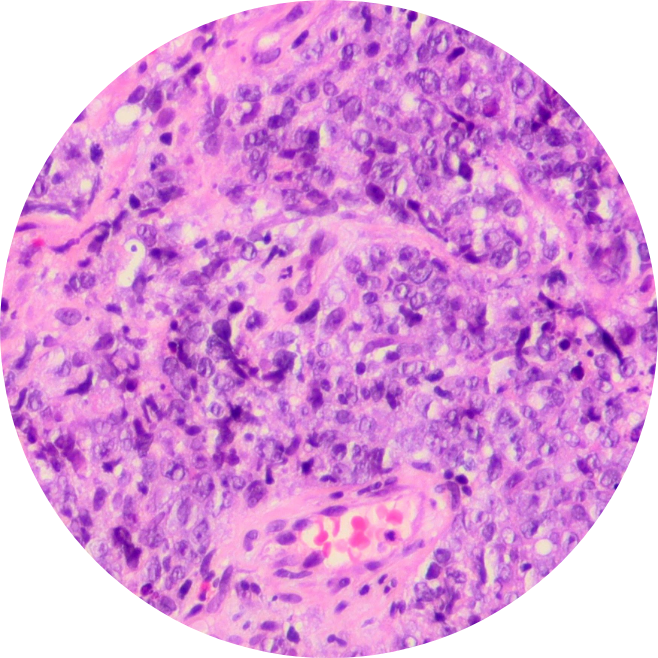

Often, a biopsy is done where a swollen lymph node is removed for testing. The sample is then tested in the lab by a pathologist to help identify the type of lymphoma and how mature it is. Imaging studies, such as X-ray scans, CT scans, MRI, or ultrasound, may also be done for a better understanding of the extent of the disease.

What are the symptoms of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)?6

Enlarged lymph nodes, or lumps, are often the first symptoms of Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma (DLBCL). Other common symptoms to look out for include:

- Swollen abdomen

- Fever

- Chest pains

- Chills

- Weight loss

- Fatigue

- Loss of appetite

- Shortness of breath

- Easy bruising or bleeding

- Severe or frequent infections

What are the risk factors of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL)?7

Risk factors refer to anything that increases one’s risk of getting cancer, but they do not determine the diagnosis as Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma (DLBCL) patients may have few or no known risk factors. According to statistics, the risk for developing DLBCL is higher in adults aged 60 and above, and in men than women.

Factors within your control

- Exposure to radiation, certain chemotherapy drugs and chemicals (such as benzene)

- Weakened immune system

- Genetic conditions (such as Ataxia-telangiectasia and Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome)

- Autoimmune diseases (such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE or lupus), Sjogren (Sjögren) disease, celiac disease (gluten-sensitive enteropathy))

- Body weight

Factors within your control

- Age

- Gender

- Family history

- Race and ethnicity

- Geography